Brief overview of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is an extensive description of mental health disorders released by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). It serves as a primary source for researchers, clinicians, health insurance companies, regulators pharmaceutical companies, as well as decision-makers.

Historical Evolution

- DSM-I (1952): The first edition, which was introduced as an adaptation of the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

- DSM II (1968): Expanded on the manual’s original scope to reflect changes in the knowledge of the mental state.

- DSM-III (1980): An important revision that included multi-axial classification as well as certain diagnostic standards.

- DSM-III-R (1987): A revised version that was updated and extended the criteria.

- DSM-IV (1994) and DSM-IV TR (2000): Introduced additional categories and text revisions.

- DSM-5 (2013): The most recent edition is notable for its decision to end the multi-axial system, as well as significant changes to several diagnoses which include autism spectrum disorders.

Purpose & Use

- Diagnostics for Clinical Disorders: Aids clinicians in diagnosing mental disorders based upon standardized criteria.

- Research: gives researchers precise definitions, making it easier to conduct research across different studies.

- Insurance and Billing: Used by healthcare professionals for billing purposes related to insurance and to ensure treatments conform to accepted diagnoses.

- Legal System: Helps with legal decisions, especially in situations where mental health issues are a factor.

Structure & Content

- Diagnostic Assessment: A list of the most commonly recognized mental disorders as well as the codes for them.

- Diagnostic Criteria Sets: Specific symptoms and durations are needed to diagnose every disorder.

- Descriptive Text: Descriptive text The Descriptive Text provides information about each disorder, including manifestation, frequency as well as risk factors, and much more.

Controversies & Criticisms

- In the past over the years, the DSM has been the subject of numerous critiques, such as allegations of influence from drug companies, concerns about how medicalization can affect normal behavior as well as debates about the inclusion or disqualification from certain diagnostics.

The DSM remains an essential part of the field of mental health. It represents the ever-changing understanding of mental health and is a vital basis to guide treatment, diagnosis, and research. But, as with every other evolving document it is subject to review, revision, and changes as the field develops and as the understandings of society about mental health evolve.

Explanation of DSM-IV and DSM-V versions.

Major Features:

- Multi-Axial System: The DSM-IV utilized a multi-axial system in order to make sure that the larger perspective of a person’s life was recorded. The system was comprised of five axes

- Axis I: Clinical conditions and illnesses that may be the focus of medical care (e.g. anxiety, depression).

- Axis II: Intellectual disabilities and personality disorders.

- Axis III: General medical conditions that could be important to diagnosing or treating a patient’s mental disorder.

- Axis IV: The psychological and environmental issues (e.g. family disputes or unemployment).

- Axis V: Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale, which gave a numerical number (0-100) about the individual’s general level of functioning.

- Inclusion of a variety of specific categories: DSM-IV had specific categories for various diseases, which allowed for a specific approach to diagnosing.

- Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR): Published in 2000, this edition did not significantly alter the criteria used for diagnosing any kind of condition. Instead, it gave greater depth, as well as information about the associated features like prevalence, course, and much more.

Critiques:

- The categorical method of DSM-IV was criticized because it did not take into account the varying nature as well as overlaps of symptoms among various disorders.

- There were concerns raised regarding the possibility of over-diagnosis due to the very specific classifications.

Major Modifications to DSM-IV

- Elimination of the Multi-Axial System: The DSM-5 was able to move out of the multi-axial model. This change was prompted by the desire to have an improved and streamlined diagnosis process that is more closely with clinical practice as well as an improved ICD system.

- Introduction to Spectrum Concepts: The spectrum of disorders previously classified as distinct in DSM-IV were merged into “spectrums that are now part of DSM-5.

- Removal and Addition of Disorders: Certain newly discovered disorders have been included (e.g., Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder) and some were eliminated or classified differently.

- Revisions to existing disorders: The majority of disorders have had their criteria changed or clarified. For example, the criteria to determine post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were made more precise.

- Dimensional Assessments: For specific diseases, physicians are now able to specify the severity, remission, or other related features that give an accurate picture of the patient’s condition.

Critiques:

- Concerns were raised regarding the broader criteria used for certain diseases, which could result in an over-diagnosis or over-medication.

- Certain people have suggested that certain modifications could reduce the number of people who can access mental health care.

While both DSM-IV and DSM-5 serve as essential tools to diagnose psychiatric illness Their methods and standards reflect the ever-changing knowledge of mental health. The shift from DSM-IV to DSM-5 marked major changes, each having its own benefits and disagreements.

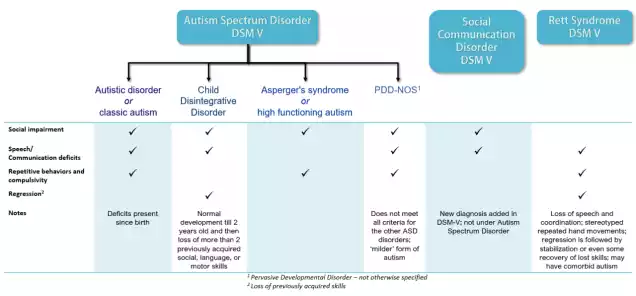

What are DSM-IV Autism Criteria?

The DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th Edition) classified autism within the category term “Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDDs).”

In this umbrella, a number of subtypes were identified, such as:

- Autistic Disorder

- Asperger’s Disorder

- Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS).

- Rett’s Disorder

- Childhood Disintegrative Disorder (CDD)

Below are the requirements for the most prominent subtypes:

Autistic Disorder

Six (or greater) things comprised of items from (1), (2) (3), and (3) including at least two items from (1) and (2), and one from both (2) and (3): (2) (3) and (3):

- Social interaction is impaired by quality. in the form of:

- Disturbance in the ability to use multiple nonverbal behaviors.

- Failure to form relations with peers appropriate to the stage of development.

- There is no desire to exchange enjoyment, passions, or accomplishments with others.

- A lack of emotional or social reciprocity.

- Communication impairments of a qualitative nature as exemplified by:

- The delay, or the total absence in spoken languages.

- People with normal speech, show difficulty in being able to start or maintain conversations with other people.

- The stereotypical and repetitive usage of language, or idiosyncratic languages.

- Insufficient variety, spontaneity pretend play, or social imitation play.

- Restricted patterning and stereotyped behaviors, interests, and actions in the form of:

- Concentration on one or more stereotyped or limited patterns of interest.

- Afraid of inflexibility when it comes to adhering to certain rituals, routines, or non-functional practices.

- Motor mannerisms that are stereotypical and repetitive.

- Constantly focusing on specific parts of objects.

Anomalies or delays in functioning must be detected before the age of 3 years and must be present in at least any of the areas listed below the social interaction area or language used in social interactions or in the form of imaginative or symbolic play.

Asperger’s Disorder

- Qualitative impairments with social communication with similar criteria to Autistic Disorder.

- Restricted pattern of repetitive and stereotyped behavior, interests, and activities with identical criteria like Autistic Disorder.

- The disorder causes significant clinical impairments in occupational, social, or other critical functional areas.

- There isn’t a clinically significant delay in the development of language (e.g. single words before age 2 years or communicative words by 3 years of age).

- There isn’t any noticeable clinically significant delay in cognition development or the growth of age-appropriate self-help abilities or adaptive behavior. fascination with the environment in the early years of childhood.

Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS).

PDD-NOS is often referred to as “atypical autism,” and was used for people who didn’t fit the precise criteria for the other disorders, but nevertheless showed significant deficiencies when it came to communication, social interaction abilities, or the presence of untrue interests, behaviors, and interests.

The DSM-IV defined the guidelines for each subtype. It also provided doctors a guidelines for diagnosing. However, the differences and overlaps between subtypes caused difficulties in diagnostics, which in part caused the change of classification in DSM-5.

What are DSM-V Autism Criteria?

The DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders Fifth Edition) the previously distinct autism subtypes of DSM-IV (i.e. autism, Asperger’s syndrome and childhood disintegrative disorder, and pervasive developmental disorders that were not otherwise defined) were merged into a common diagnosis

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

The criteria used to diagnose Autism Spectrum Disorder within the DSM-5 are in the following order:

- Persistently deficient in social interactions and communication across different situations as exemplified by the following issues, either in the present or through history:

- Inadequate social-emotional reciprocity: The range of options includes:

- Unusual social style and the inability of normal back-and-forth conversation.

- Less sharing of interest emotional, affect, or.

- Inability to initiate social interaction or to respond.

- Communication deficits that are nonverbal are used to facilitate social interaction: The range of options includes:

- A lack of integration between verbal and nonverbal communication.

- Anomalies in eye contact or body language.

- A lack of understanding and a lack of usage of hand gestures.

- There is a complete absence of facial expressions or non-verbal communication.

- Inadequacies in building understanding, sustaining, and maintaining relationships: The range of options includes:

- The difficulty of adapting behavior to different social situations.

- Troubles sharing creative play with others or making friends.

- There is a lack of curiosity among peer groups.

- Restricted pattern of behavior that is repetitive activities, interests, or patterns: Which are manifested in a minimum of two or more of these in the present or through history:

- Motor movements that are stereotypical or repeated: Using objects as well as speech (e.g. simple echolalia, motor stereotypies, repeated use of objects, or idiosyncratic expressions).

- Constantly pursuing identicality: Rigid commitment to routines, ritualized patterns of nonverbal or verbal behavior (e.g. extreme dismay when a small change occurs, issues with transitions, rigid thought patterns, greeting routines that require you to follow the same way or eating the same food each day).

- Highly restricted, fixed pursuits: These are unusual in their intensity or focus (e.g. the strong connection or obsession with odd objects, or excessively narrowed or persistent interests).

- Hyper and hypo-reactivity: To sensory inputs or heightened interest in things that are sensory (e.g. evident indifference to temperature or pain and a reluctance to certain sound or texture, excessive scent or touch of objects, an attraction to light or motion).

- The symptoms must be evident at the beginning of developmental time: (But they may not be fully evident until the demands of society surpass the capacity of the individual or are disguised by strategies learned in later life).

- Signs and symptoms can cause significant clinical impairment: In occupational, social, or other critical areas of functioning.

- These problems are not more easily explained: Through intellectual impairment (intellectual disorders of development) or general developmental delay.

Severity Levels in DSM-V:

The DSM-5 also added different levels of severity for this ASD diagnosis:

- 1. (Requiring the support)

- 2. (Requiring significant support)

- Level 3 (Requiring very substantial support)

Each level is determined by the severity of impairment in social communication and the repetitive, restrictive behaviors.

It’s important to understand that the DSM-5 classification was reclassified to give an accurate and simplified diagnosis of autism. It reflects the fact that the autism spectrum manifests, rather than distinct subtypes.

The Major comparison chart of DSM IV and DSM V Autism

Comparison Chart: DSM-IV vs. DSM-5 Autism Criteria

| Criteria/Aspect | DSM-IV | DSM-5 |

|---|---|---|

| Main Classification | Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDDs) | Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) |

| Subtypes | – Autistic Disorder – Asperger’s Disorder – PDD-NOS – Rett’s Disorder – Childhood Disintegrative Disorder |

All subtypes combined into a single category: Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| Social Impairments | Separate criteria for impairments in social interaction. | Combining into one category: “Persistent deficits in social communication and interaction”. |

| Communication Impairments | Separate criteria for impairments in communication. | Integrated into the social deficits criteria, emphasizing the interconnectedness of social interaction and communication. |

| Repetitive Behaviors & Restricted Interests | The specific set of criteria detailing various behaviors. | Repetitive or restrictive patterns of behavior, interests or activities. |

| Age of Onset | Symptoms need to be present before age 3. | Symptoms must be present in the early developmental period. |

| Diagnosis Based on Axes | Used a multi-axial system. | Eliminated the multi-axial system. |

| Severity | It is not specified in the context of the autism diagnosis. | Introduced levels of severity: Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3. |

| Sensory Issues | Not explicitly mentioned as a diagnostic criteria. | Included hyper- or hyporeactivity to sensory input as a diagnostic criterion. |

| Coexisting Intellectual/Developmental Delays | Separate diagnoses. | Disturbances are differentiated from intellectual disability and global developmental delay. |

This chart highlights some of the major differences between the DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria for autism. The transition from DSM-IV to DSM-5 aimed to reflect the growing understanding of autism as a spectrum and to streamline the diagnostic process by removing subtypes that were difficult to differentiate reliably.

Similarities between DSM IV and DSM V Autism

It is important to note that the DSM-IV as well as the DSM-5 diagnosis criteria of autism while differing in a variety of ways, have a few similarities in their understanding of and characterization of autism.

These are the main similarities:

- Core Features of Autism: The two editions focus on the two primary areas of autism:

- Communication and social impairments.

- Limited, repetitive, and restricted activities.

- The Early Developmental Onset: both the DSM-IV and DSM-5 indicate that the symptoms of autism can be observed from the beginning of childhood. The DSM-5 permits an empathetic definition of when the symptoms begin to manifest.

- Significance of symptoms: Both versions emphasize that, for a diagnosis to be considered the symptoms have to cause “clinically significant impairment” in different aspects of functioning.

- The Exclusion of Other Conditions: Both versions state that if the signs can be explained better by another medical condition the diagnosis of autism may not be the best option.

- Recognizing Spectrum: Although the DSM-5 more officially accepted its “spectrum” terminology with “Autism Spectrum Disorder,” the DSM-IV’s inclusion of a variety of types under “Pervasive Developmental Disorders” also recognized the diversity and variety of severity and symptoms in autism.

- Notable behavior and symptoms: A variety of particular symptoms and behaviors described by the DSM-IV criteria are carried over to the DSM-5 although they could be classified or phrased differently. Examples include difficulties with nonverbal communication and lack of social reciprocity or repetition of usage of objects or words (like echolalia) as well as a heightened attention to specific desires.

- Comorbidity Recognition: Both versions acknowledge that there are other conditions that can co-occur with autism, including cognitive impairments, seizures of the language, and epilepsy, to name a few.

- The need for Comprehensive Assessment: Both versions of the DSM insist on the need for an extensive and thorough evaluation for determining a diagnosis considering the range and complexity of autism-related manifestations.

Although the diagnostic criteria went through significant changes and refinements from DSM-IV to the DSM-5 The fundamental understanding that autism is a neurological disorder that is characterized by challenges in communication with others and repetitive behaviors is the same across the two. These changes reflect a growing understanding of autism that is based on the latest research as well as clinical experience and feedback from communities.

Controversies and Implications

The change from DSM-IV and the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism was not without its fair share of controversy and ramifications. A lot of them stemmed from changes to diagnostic criteria the fusion of subtypes and the concern about eligibility for service.

Here’s the outline:

Controversies:

- Elimination of Subtypes:

- A decision made to drop the Asperger’s Disorder category as a separate Disorder and to integrate it into the larger Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) attracted a lot of attention. A lot of people diagnosed with Asperger’s Disorder were identified closely with the diagnosis and were worried about losing their status or having to face an identity change.

- The ambiguity and broader nature of the diagnosis for PDD-NOS in DSM-IV has led some to believe it was a positive step. The DSM-5 method was a step in the right direction, while others were worried about the people who could “fall through the cracks.”

- New Severity Levels:

- The introduction of the severity level is intended to help clarify the degree of care an individual may require. Some critics were concerned that the classifications could become too rigid or not accurately reflect the individual’s changing needs in the course of time.

- Sensory Issues:

- Although the acceptance of sensitivities to sensory within the DSM-5 was perceived by many as an important step that was reflective of the experiences of many people who have autism, some were worried about whether this could be accurately diagnosed or if it could result in overdiagnosis.

- Age of Onset:

- Moving from a fixed age (before three years for DSM-IV) into something called an “early developmental period” in DSM-5 was viewed as unclear by some, despite the fact that it was designed to recognize that not all signs of illness appear until age 3.

Implications:

- Service Eligibility:

- One of the biggest concerns was the possible effect on eligibility for service. Due to changes in diagnostic criteria, There was a concern that certain individuals, especially those who were previously diagnosed with PDD-NOS or Asperger’s could no longer be eligible to receive services.

- Research Comparisons:

- As the diagnostic criteria, clear comparisons between studies done before and after DSM-5 may be difficult. It could complicate understanding of the prevalence of autism and its development as it progresses.

- Public Perception:

- The amalgamation of all autism subtypes into one “spectrum” could lead to an increased awareness and acceptance of autism’s diverse nature among the general public. There are those who worry that it could result in oversimplifications or misconceptions regarding the condition.

- Identity and Community:

- For many people, a diagnosis isn’t simply a medical label, it’s an integral element of their identities. The demise of subtypes such as Asperger’s triggered discussions within the broader community on the meaning of labels, identity, and the meaning of labels and names.

- Clinical Practice:

- The new criteria required adjustments and retraining for many physicians to be able to understand and use the new criteria efficiently. The changes also highlighted the significance of clinical judgment due to the broader flexibility of certain criteria.

Although the DSM-5 was designed to improve and simplify the diagnosis of autism based on the evolving knowledge of science, its modifications did not come without controversy and large implications for people as well as family members as well as clinicians, researchers, and policymakers.

Conclusion

The shift from DSM-IV and the DSM-5 criteria for autism led to major changes in how the disorder is recognized and recognized. While the DSM-5 tried to offer a more precise depiction of the spectrum that autism is it also consolidated subtypes as well as changes in the diagnostic criteria caused a number of controversies and consequences.

There were a variety of concerns ranging from identity and community identity to the eligibility for services and clinical practice adjustments. In spite of these issues, the evolving diagnostic criteria reflect the constant attempt to comprehend and serve the diverse autism spectrum.

References books

- “The Autism Spectrum: Scientific Foundations and Treatment” by William O’Donohue and Sara Jane Webb

- An overview of the science behind autism spectrum disorders and their treatment.

- “NeuroTribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity” by Steve Silberman

- A comprehensive history of autism, discussing the evolution of its diagnosis and society’s changing perspectives on the condition.

- “The Complete Guide to Asperger’s Syndrome” by Tony Attwood

- A seminal text on Asperger’s Syndrome, offering deep insights into the condition, its diagnosis, and its implications.

- “DSM-5 Handbook of Differential Diagnosis” by Michael B. First

- A guidebook that offers a structured approach to diagnosing disorders using the criteria of the DSM-5, including autism spectrum disorder.

- “A Parent’s Guide to High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder” by Sally Ozonoff, Geraldine Dawson, and James C. McPartland

- An informative resource for parents seeking to understand autism’s nuances, especially as the diagnostic landscape has shifted.

- “Uniquely Human: A Different Way of Seeing Autism” by Barry M. Prizant

- A perspective on autism that emphasizes understanding and celebrating the unique qualities of individuals with ASD.

- “The Science and Fiction of Autism” by Laura Schreibman

- This book offers a comprehensive look at what we know about autism, debunking myths and clarifying the reality of the condition.

For academic purposes or to delve deeper into the DSM’s evolution and the specifics of its criteria, it would be essential to consult the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” in its various editions, especially the DSM-IV and DSM-5.